Three Tools for Inclusive Innovation

IDIN Network members are using, adapting and creating tools to engage others in problem solving. Photo credit: Omar Crespo

In an earlier post, I mentioned that one of the functions of an innovation ecosystem is to engage diverse people in problem solving. In case you missed it:

In a thriving local innovation ecosystem, diverse individuals and institutions can access skills and tools for problem solving, collaborate with each other, obtain feedback, iterate, learn, and share with others.

Here at the Australia Fellows workshop, I was hoping to hear some examples of tools from around the world that promote this kind of engagement. I was not disappointed.

Here are three stories of how IDIN innovators have used, adapted and created tools to engage others in problem solving. These tools facilitate co-creation, prototyping, and dissemination – three crucial steps in any innovation process. Put simply, these tools start conversations, bring ideas to life, and spread solutions far and wide.

Read on to find out how a cardboard box, a printer, or a “record” button can be like a blank canvas: an invitation to create and change the world around you.

The Story Cube: Starting conversations

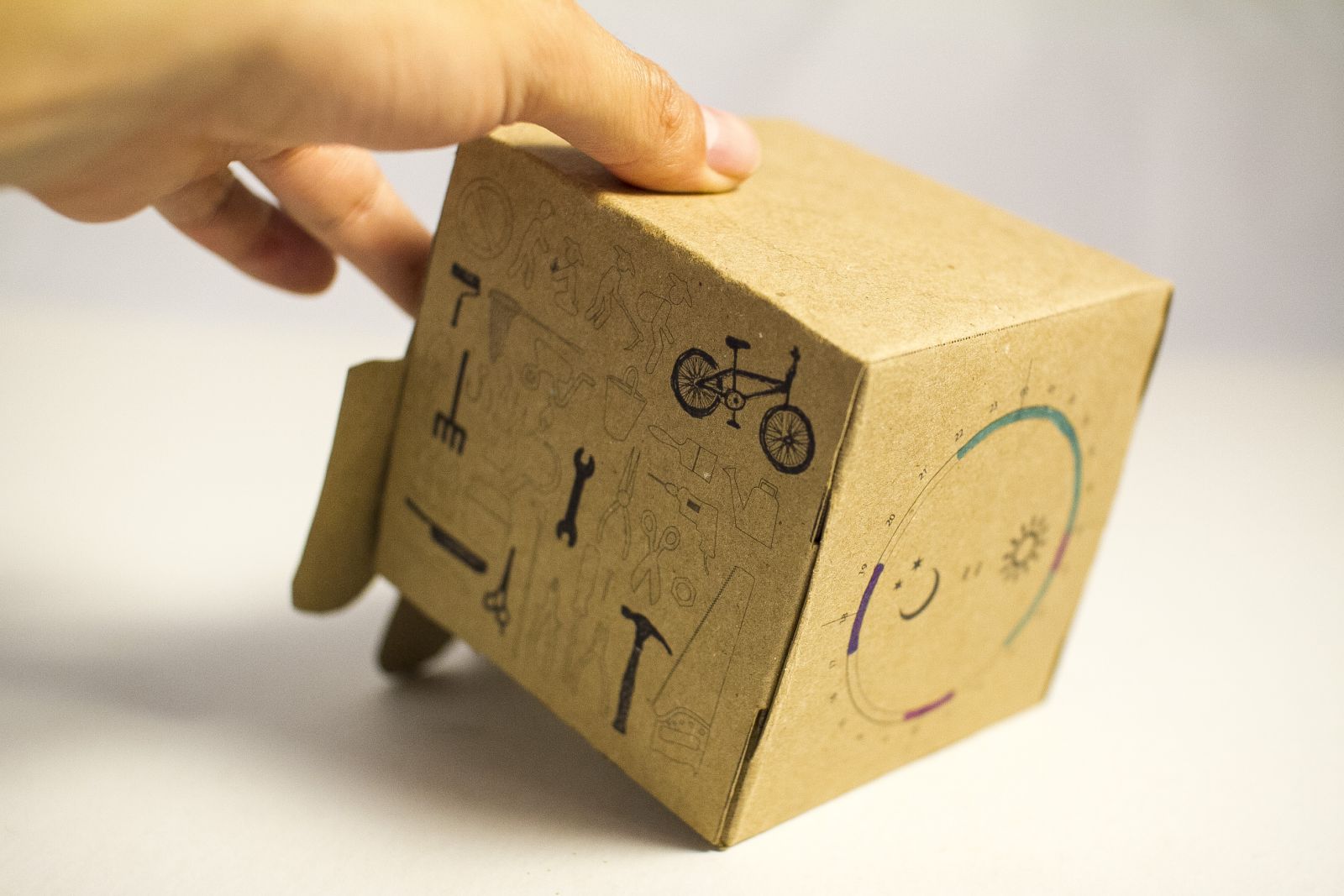

The Story Cube features six conversation starters that lay the foundation for co-creation between a designer and a user. Photo credit: Omar Crespo

When the IDIN Guatemala chapter received a grant to run design workshops in communities surrounding Lake Atitlán, they were keen to get started right away. With IDDS Hogares Sostenibles on the horizon, the chapter was eager to build bridges with community members and begin to co-create solutions to their everyday challenges.

But in the first workshop, the team quickly came up against barriers. The terms they used in their workshop didn’t seem to resonate with the participants. Their diagram of the design cycle drew blank looks. After that first workshop ended, the team went back to the drawing board. In a flurry of Post-It notes, they “unlearned” their old approach to co-design and came up with a new strategy to engage community members.

What they came up with is deceptively simple: a cardboard box. On each of the six sides is a conversation starter. One side has the broad outlines of a face, and invites the participant to draw a self-portrait (stencils are provided for shyer artists). Another side features an array of tools – hammers, sewing machines, computers, and more – and invites participants to color in the skills they have. A third invites them to illustrate a typical day. By the end of the conversation, the facilitator has a detailed picture of the participant’s life, abilities and challenges. The stage has been set for co-creation.

Crucially, it’s not just the participant who completes a cube. The facilitator does it, too. This sets up a two-way conversation in which both are sharing their stories and building a relationship, instead of the facilitator simply extracting information from the participant.

The Affordable 3D Printer: Bringing ideas to life

AB3D’s recycled e-waste printer makes prototyping and manufacturing accessible to makers in Kenya. Photo credit: AB3D

Roy Ombatti first learned the power of 3D printing during his days as a student at the University of Nairobi, where he designed a custom printed shoe for people whose feet had become deformed due to jigger infection. He began to imagine a world where every person had the ability to bring his or her ideas to life.

The problem? 3D printing technology is expensive. In Kenya, a 3D printer costs $1000 or more - far more than most artisans, teachers, or entrepreneurs are able to pay.

Roy saw an opportunity. In 201X, he launched African-Born 3D Printing, or AB3D. AB3D builds low-cost 3D printers from recycled e-waste and sells them to schools, makerspaces, and companies. The printing filament is also low-cost and environmentally friendly– it comes from recycled PET bottles. In addition to building and selling printers, Roy teaches workshops on 3D printing at local schools, sharing this technique with the next generation.

Karl Heinz Tondo, who co-founded AB3D, wants to take this vision back to his home country of Cameroon. He has founded a spinoff, Juakali Box, with the goal of “creating many Roys.” He envisions a country full of “digital blacksmiths” who design and print products locally rather than importing them from abroad.

By expanding access to 3D printing, both Roy and Karl hope to make local prototyping and manufacturing a possibility for African students, artisans and entrepreneurs.

Baang: Spreading ideas

Baang, a voice-based social media platform, allows people to share ideas widely regardless of their literacy level. Photo credit: Rah-e-maa

At IDDS Lahore in January 2016, Sacha Ahmed’s design team had hit on an idea. Most efforts to promote better maternal health care in Pakistan were directed at mothers, who often didn’t have financial decision-making power in the household. What if they tried reaching fathers instead?

Rah-e-maa was born. The team interviewed users, crafted their content (“If you spend X rupees on vitamins now, you’ll save X rupees in costs to treat X later!”], designed the interface, and wrote up a report.

Now, they just needed a way to reach their target audience. The team was hoping to reach fathers from low-resource communities, where literacy levels are low and where few have access to TVs, computers or smartphones. With these barriers, how could they reach enough fathers to move the needle on maternal health?

That’s where Baang came in.

Built off the Polly platform, Baang, which means echo, is described as “Reddit for voice.” After calling in to the number, you can record a Baang and listen to other people’s Baangs: in Pakistan, Baangs range from greetings to jokes to songs to Qu’ran verses. As with any social media platfom, you can also like, comment, or share Baangs. The platform’s inventors launched it by giving the phone number to seven janitors at Information Technology University. Within 71 days, 42,500 calls had been made.

Baang opened up a world of possibility for the Rah-e-maa team. Building on top of the platform, Sacha’s team designed an interface where fathers could access recordings of maternal health information from “Dr. Saba,” receive audio “nudges” about maternal care, interact with other fathers, and offer feedback to Sacha’s team.

This platform is a game changer for disseminating ideas and solutions in communities that might otherwise be cut off from that type of access. What’s more, it invites the fathers themselves to be part of the solution.

What tools have helped you engage people in problem solving? How have you adapted them for your own work? Leave us comments on our Facebook page!

Laura Budzyna is the Monitoring, Evaluation & Learning Manager for the International Development Innovation Network, headquartered at MIT D-Lab.

Related blogs: